Dear Great-grandma Mary,

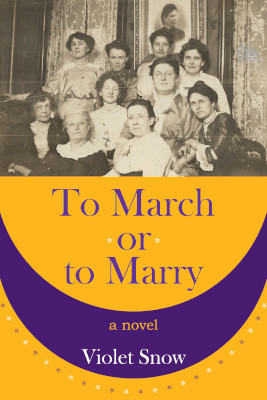

I am so pleased with the new direction our collaboration is taking. This phase began with the talented Jami D, who sings in a Fleetwood Mac cover band and is conscious of the power of costume. She suggested I get a 1910s outfit to wear when I give presentations about my book, To March or to Marry, a historical novel about suffrage and women’s clubs.

I started looking for one of those long white dresses the suffs used to wear to marches. Nothing affordable was to be found, but in my closet I discovered a skirt and jacket that approximated the style of the suits of a century ago. Performer and hat-maker Mindy Fradkin, a.k.a. Princess Wow, trimmed a hat with fabric, netting, a pin, a bow, and a purple plume, and voilà, I could pass for either a suffragette or a clubwoman. I wore it to a women’s club convention where I was selling books, and the outfit was a hit–especially the hat.

Last week, I made plans to dress up for a Phoenicia Library Zoom reading, and it seemed odd to appear in that get-up as myself. Why not go as you, since one of the protagonists is the book is based on you? And you were so obliging, furnishing words for me to say, as well as sly little jokes like the ones you were fond of inserting into your writings. I had a grand time, and you seemed to enjoy your venture into the 21st century. At last I can apply those years of amateur acting at the Phoenicia Playhouse.

From now on, I plan to have you substitute for me every time I give a talk about the book. (“Violet Snow has been unavoidably delayed, so her great-grandmother has offered to speak in her place.” That’s how I’ll be introduced to the Daughters of the American Revolution, Peter Minuit Chapter, on November 1.)

When I was reading your travel diary and your letters, I had such a longing to know you, and I wished I had been around when you were alive. By writing this book, which draws so much from your letters, I had the chance to spend time with you, and now we are getting even closer. You are such a lively companion! Thank you for saving all those letters, announcements, your marriage certificate, your sons’ report cards, my grandmother‘s baby book (even though it’s slightly creepy to touch the fine blonde hair clipped from the head of my grandmother when she was a baby). I have so many ways of getting to know you. Now I can even be you for an hour at a time. What a joy!

Love, Violet

Note to readers:

To order To March or to Marry in paperback or eBook, click here.

Check out this article on how my great-grandmother, Mary Wingebach, became a character in my novel, from Best Self magazine: https://bestselfmedia.com/feminism-for-the-ages/

And you are invited to tune in to a livestreamed show on Sunday, October 24, at 7 p.m., as the incisive Betty MacDonald interviews Mary Wingebach, who will also read from To March or to Marry: https://greenkill.substack.com/p/words-carry-us-with-betty-macdonald-52f

#bestself #bestselfmag #bestselfmedia #suffrage #suffragette #ancestors #historicalnovel #historicalfiction

As U.S. women were struggling toward the vote, and World War I was nearing its end, an

As U.S. women were struggling toward the vote, and World War I was nearing its end, an

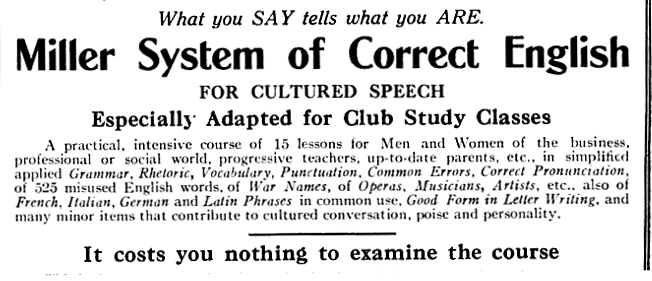

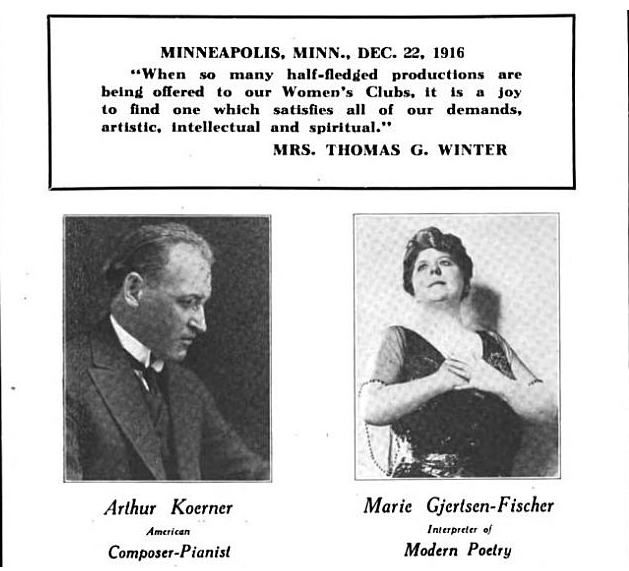

Self-improvement clubs focused on subjects that were literary or related to home life. Other clubs were devoted to social reform in the period when women’s consciences were provoked by the spread of poverty and

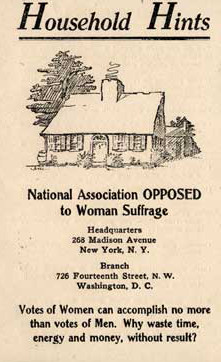

Self-improvement clubs focused on subjects that were literary or related to home life. Other clubs were devoted to social reform in the period when women’s consciences were provoked by the spread of poverty and  It’s hard for us to imagine, in the modern world, that there were women who were aware of the suffrage movement in the 1800s and early 1900s and yet were not interested in gaining the right to vote. In fact, most of the leaders of anti-suffrage organizations were women. Most

It’s hard for us to imagine, in the modern world, that there were women who were aware of the suffrage movement in the 1800s and early 1900s and yet were not interested in gaining the right to vote. In fact, most of the leaders of anti-suffrage organizations were women. Most

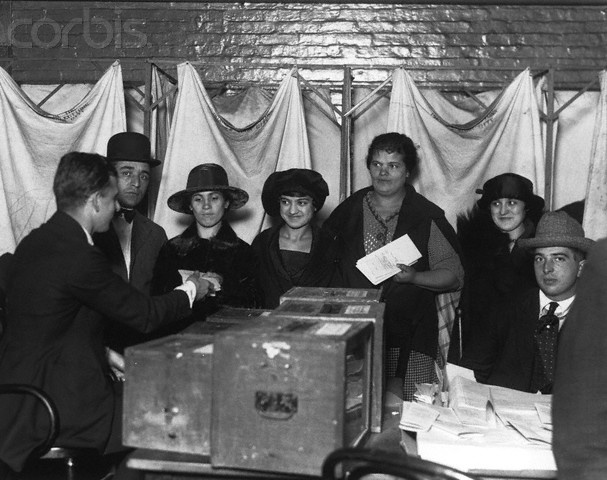

Before the commercialization of Christmas took hold, before the Easter bunny was born, and before Thanksgiving became a pig-out, Election Day was America’s big, festive holiday. Amid the Election Day celebration of 1899, my great-grandparents’ courtship began.

Before the commercialization of Christmas took hold, before the Easter bunny was born, and before Thanksgiving became a pig-out, Election Day was America’s big, festive holiday. Amid the Election Day celebration of 1899, my great-grandparents’ courtship began. Here is a podcast of my short story, “The Halfway Café,” narrated by a dead woman and examining such questions as: Do our ancestors watch us? Why would they care if we mourn? An outtake from my mystery novel, Stone’s House, it is based on beliefs of indigenous people about the persistence of consciousness after death. The story opens:

Here is a podcast of my short story, “The Halfway Café,” narrated by a dead woman and examining such questions as: Do our ancestors watch us? Why would they care if we mourn? An outtake from my mystery novel, Stone’s House, it is based on beliefs of indigenous people about the persistence of consciousness after death. The story opens: